June 2023

As I travel through the world, one of my favorite lens to view it through is that of its’ ancient inhabitants. The groups of people who have lived in a given place for a long, long time. This often looks like studying ancient civilizations, and then using that as a springboard to understand how the modern-day descendants of those ancient people live today.

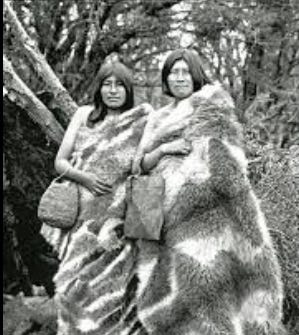

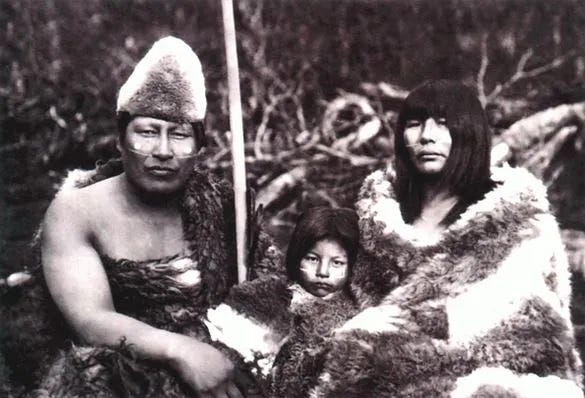

The curiosity arises so naturally. Going to Patagonia, for example. Sure, the stunning landscapes and outdoor recreation opportunities are enough of a reason to go. But I always find myself wanting more, a deeper understanding of these places. Like, an understanding of how on earth humans actually survived somewhere as harsh as Tierra del Fuego before modern technology. So I go to a museum and learn that the Yaghan group of this region had fires constantly burning in their canoes and on land, used guanaco nerves to sew the guanaco skins into clothing and whittled the bones into needles. Resourcefulness and land usage is fascinating to me, so learning bits like that scratches the itch, the incessant questions that I always have of how the world used to work.

My constant hunt for knowledge of how humans have evolved in relation to their environment continued when I arrived to the western Mexican state of Jalisco (if you haven’t heard the name before, the state is famous for being the birthplace of tequila, and it’s also got Puerto Vallarta on its’ coast).

I was aware that the peyote cactus, or hikuri, was endemic to this region. It was something I had been curious about for a while, but I don’t tend to go out of my way to seek out plant medicine. Rather, I have this feeling of trust that when the time is right, the moment will find me.

And that’s how I felt when one day during my month-long stay in Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco, an opportunity arose to join a women-only ceremony led by a Wixárika priestess (Also known as Huichol, this is the group indigenous to the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range in Western Mexico).

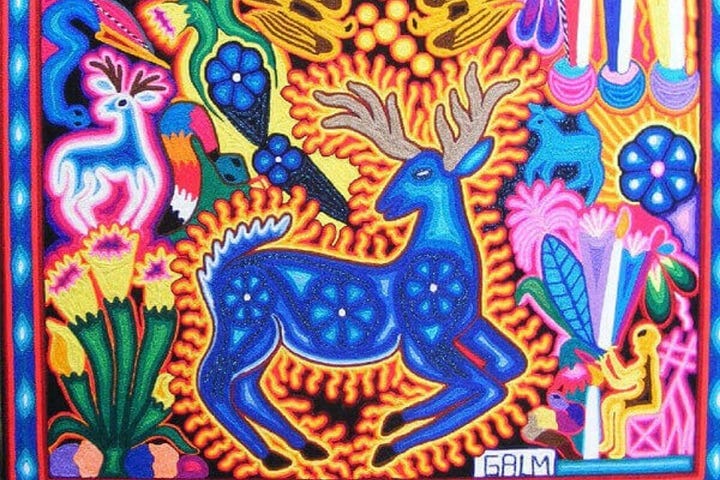

The psychoactive compound found in the peyote cactus is mescaline. Psilocybin is to hallucinogenic mushrooms as mescaline is to the peyote cactus. Akin to the use of hallucinogens in cultures all over the world, the cactus is used by the Huichol people as a conduit for connecting the spirit world and material world. It is a tool to access the divine, and is seen as the material representation of the Huichol’s guiding spirit, a blue deer. The Wirikuta desert, a sacred region for the Huichol people located in Jalisco’s neighboring state of San Luís Potosí, is the site of yearly pilgrimages to collect the cactus for their ceremonies. This desert is the setting of the Huichol’s origin story.

The legend goes that a long time ago, humans were struggling to survive in a land blighted with droughts, famines and disease. Some elders sent out four young men (each one signifying one of the four elements) to hunt for something to bring back to the community. After some time, the men spotted a blue deer and began chasing it. The deer lead them into the Wirikuta desert, and eventually disappeared into the place where the spirit of the earth lives. In it’s place, the men discovered a deer made of peyote cacti. The men took the cacti back home, and the elders recognized that it could be fed to their community to quench their physical hunger and spiritual thirst. So in this way, consuming hikuri is their form of connecting to the spirit that saved them, and through this connection, ensuring their physical and spiritual protection. It is a healing modality that strengthens community bonds.

This video gives you an idea of the land this group comes from and their traditional dress and customs:

Peyote is sought out by us, people living modern lives, as a way to get to know ourselves on a deeper level and understand our place in the world. The desire for these insights is what began my usage of hallucinogens when I was 20, and now, days after turning 27, I felt that now was the moment to try peyote.

The day of the ceremony, I packed my overnight bag with warm clothes, a pillow from my co-living house, some snacks, and my notebook, and took off into Guadalajara’s city center where one of the women was going to pick me up. It was held in a suburb tucked away about an hour outside of Guadalajara. We drove to the outskirts of the city to a house in a hilly neighborhood with a big yard looking out to the gently folding, bone-dry foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental.

We arrived as the sun was beginning to set, and met the marakame (similar to a shaman, the elder who leads the ceremony), and her daughter, who would be acting as kind of a liaison between her mother’s traditional leadership and the attendees. Almost all of the other women who attended were from Guadalajara; a woman from England and I were the only foreigners from outside Mexico. But that night, all of us were united in our foreign-ness to this ancient indigenous tradition.

In Mexico, the indigenous populations uphold their traditions and customs relatively strongly and fiercely. The Huichol people are no exception. I could see this reflected in the ceremony itself. In contrast with the ayahuasca ceremony I had participated in years before with a Colombian shaman, this ceremony was much more structured.

The ayahuasca ceremony was somewhat of a free-for-all, with some of us (me) having an entire experience in our own heads, huddled in our sleeping bags half the night, minds racing, pens scribbling, while others were all over the place, with one woman stripping off all her clothes and running around with the feeling that a demon was being exorcised from her. Others were getting up for the bathroom constantly to purge out of both ends, dance to the icaros (traditional shamanic songs) by the bonfire, sob uncontrollably, and talk to each other. Generally, there was a laissez-faire attitude that whatever you needed to do, you did (to clarify, the woman who took off her clothes was quickly aided with a big blanket to cover up and attention from the shaman to guide her through).

In contrast, the hikuri ceremony had rules. If you wanted to go to the bathroom, you had to speak up and ask the marakame’s permission. If granted, you then had to exit the circle counterclockwise and enter back again to your spot in a clockwise direction. It was highly encouraged to instead just wait until the marakame decided to give everyone a break to get up all at once, avoiding individual trips and therefore disruption to the energy of the group. At the ayahuasca ceremony, after the first cup taken together, more cups were given to different people at different times to match each person’s unique needs. Here, the ceremony facilitators brought around a bowl of fresh cactus for us to eat at certain moments, and in those moments it was strongly advised that we consume what we were given, regardless of how woozy or nauseous we might feel.

So, as we sat in a circle around the bonfire once the sun had set, I glanced at my bag tucked away in a corner away from the group, my bag that held my precious journal. I began to realize that there would be no furious scribbling tonight, no defying of hand cramping in a valiant effort to match the speed of my pen to the runaway train of though in my head. The environment here was less about fully retreating into your own world, and more about sharing and finding synchronicity as a group. Letting the train of thought and feeling run up your vocal chords and out of your mouth instead of silently onto paper. First discomfort identified - I’ve always had a hard time doing this in groups, preferring instead to channel my thoughts into writing. But I was determined to meet this tradition where it was at, and learn what I could from it, so I settled into the experience with an open and willing mind.

After a couple rounds of cactus-eating and a couple hours of listening to the marakame chanting in the Huichol language as her daughter translated into Spanish for us, I started to feel that full-body roller-coaster sensation that tends to comes with the onset of hallucinogens, especially when it is my first time with a substance and I am not sure what to expect. It’s the feeling that you are on the precipice of something. You aren’t fully tripping yet, but you feel something shifting in your body. A wave of change that you know you have to surf, you have to allow, because trying to resist it will lead to nothing good.

Much of the ceremony, we sat in silence while the marakame and her daughter sang, chanted and spoke, and while the daughter’s husband (the only man in attendance) tended the fire. For much of the first part of the night, I had been feeling kind of clammed-up. A lot of the other attendees were in their 40s and above, and it struck me how much more life they had all lived than me. A lot of their anecdotes were about commitment to the families that they have created, a subject that that they all seemed to be bonding over, and of which, as a single solo traveler, it was hard for me to really relate to.

Meanwhile I was thinking about my psychic wounds, my demons, things I am trying to heal. It felt like it would be out of place to share them, to share the dark night of my soul while the group sentiment was more focused on love and gratitude. Gratitude isn’t the first word I’d use to describe what I was feeling in that moment. Yes, I felt grateful to be there, but my mind was mostly on other, heavier topics, so that it would’ve felt disingenuous to speak in that moment about my depths of gratitude like the other women. So hours passed and I said nothing.

One of the moments that finally encouraged me to speak was when the marakame’s daughter and her husband spoke about how their relationship is a journey of growing together and witnessing the best and the worst sides of each other, encouraging each other to foster the best in themselves. Even though I am single, I felt a connection with their vulnerability and willingness to acknowledge the “ugly” sides of themselves. It was one of the first moments that I really felt a deeper connection with the group.

Still, the general lack of engagement and connection I felt for much of the night made me wonder for a while why I sometimes feel so dissociated from certain groups. Sometimes I feel like a perpetual outsider, and I get the sense that I seem that way to others as well, which just makes the whole thing feel worse. But the next morning as I headed back to the city with the British girl Mar and shared these feelings with her, she looked surprised and replied that I didn’t seem at all out of place at all, and was very well spoken during the ceremony. It made me wonder if I have a warped perception of myself and my “otherness.”

This feeling of estrangement manifested in my thoughts on a macro scale as well. As I struggled to make sense of the chants and the symbolism behind everything happening in the ceremony, I began wondering what the purpose of all of us being here was in the first place. The ceremonial usage of this cactus is not in our DNA (at least, certainly not in mine as a descendant of northern Europeans). Should I even be here? The whole purpose of the ceremony is for the Huichol people to connect with their ancestors and bond as a community, and to foster open communication. But here we were, a group of strangers, sharing in a sort of bastardization of the “real thing”. “Is there a point in this?” I thought to myself at one point.

But in this fragmented world, maybe these moments of connection are more paramount than ever. No, its not the “real” thing in the sense that we are not Huichol people sitting in our community, but does that mean its not significant? Maybe experiences like these are opportunities to learn from these communities that fight to keep their ways of life, to be given a glimpse into their irreplaceable customs. It’s a way to support with your presence the precarious path these groups walk through the industrialized modern world that generally runs anathema to their entire worldview. I guess in that way its sort of like eco-tourism or something. Or maybe that’s just my inner cynic talking.

For a while during the ceremony I was thinking about my best friend Natalie, and how much I value our relationship. Reminiscing about and feeling gratitude for that friendship is my mental comfort zone. Then I noticed how it’s less comfortable for me to turn to thinking about my relationship with myself. I’ve always been an introverted person with a rich inner world and self-relationship, but that doesn’t mean that observing that relationship is always a walk in the park. I guess here in lies the heart of these plant medicine experiences for me and the value I always seem to find in them. A night to remove yourself from your normal state of consciousness and awareness, and allow new understandings and realizations to flourish.

Sources:

https://chacruna.net/hikuri_peyote_conservation/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Huichol

https://lolomercadito.com/blogs/news/wixarika-culture-kauyumari-the-legend-of-the-blue-deer